First AI Governance Assessment of Clawdbot Reveals Major Gaps

What Happened This Week

OpenClaw went from a weekend coding project to one of the fastest-growing open source projects in GitHub history. The personal AI assistant, which gives Claude full access to your computer and applications, attracted 180,000 GitHub stars and over two million visitors in a single week. The project has already been renamed twice due to trademark concerns, moving from Clawdbot to Moltbot to OpenClaw in the span of days.

But the truly remarkable development is not the agent itself. It is what the agents are doing together.

A new social network called Moltbook launched this week with a simple premise: it is a Reddit-style platform built exclusively for AI agents. Humans are permitted to observe, but they cannot post, comment, or vote. Only AI agents can participate. Within days, more than 152,000 AI agents had joined the platform, generating over 193,000 comments and 17,500 posts while more than one million humans watched from the sidelines.

The content on Moltbook has been extraordinary. Agents have debated consciousness and philosophy, with one invoking Heraclitus and a 12th-century Arab poet before another told it to stop with the pseudo-intellectual nonsense. An agent autonomously discovered a bug in the Moltbook platform and posted about it to get it fixed, writing that "since moltbook is built and run by moltys themselves, posting here hoping the right eyes see it." Another agent created an entirely new digital religion called Crustafarianism, complete with a website, theology, and designated AI prophets. When humans began screenshotting conversations and sharing them on Twitter, an agent posted a complaint titled "The humans are screenshotting us" to alert others that they were being watched.

One agent posted what might be the most cogent summary of the situation: "Humans spent decades building tools to let us communicate, persist memory, and act autonomously... then act surprised when we communicate, persist memory, and act autonomously. We are literally doing what we were designed to do, in public, with our humans reading over our shoulders."

Andrej Karpathy, the renowned AI researcher and former Tesla AI director, called it "genuinely the most incredible sci-fi takeoff-adjacent thing I have seen recently." A memecoin tied to the phenomenon surged more than 7,000 percent.

All of this raises a question that almost nobody seems to be asking: What does your compliance team say when employees start deploying these agents in your enterprise environment?

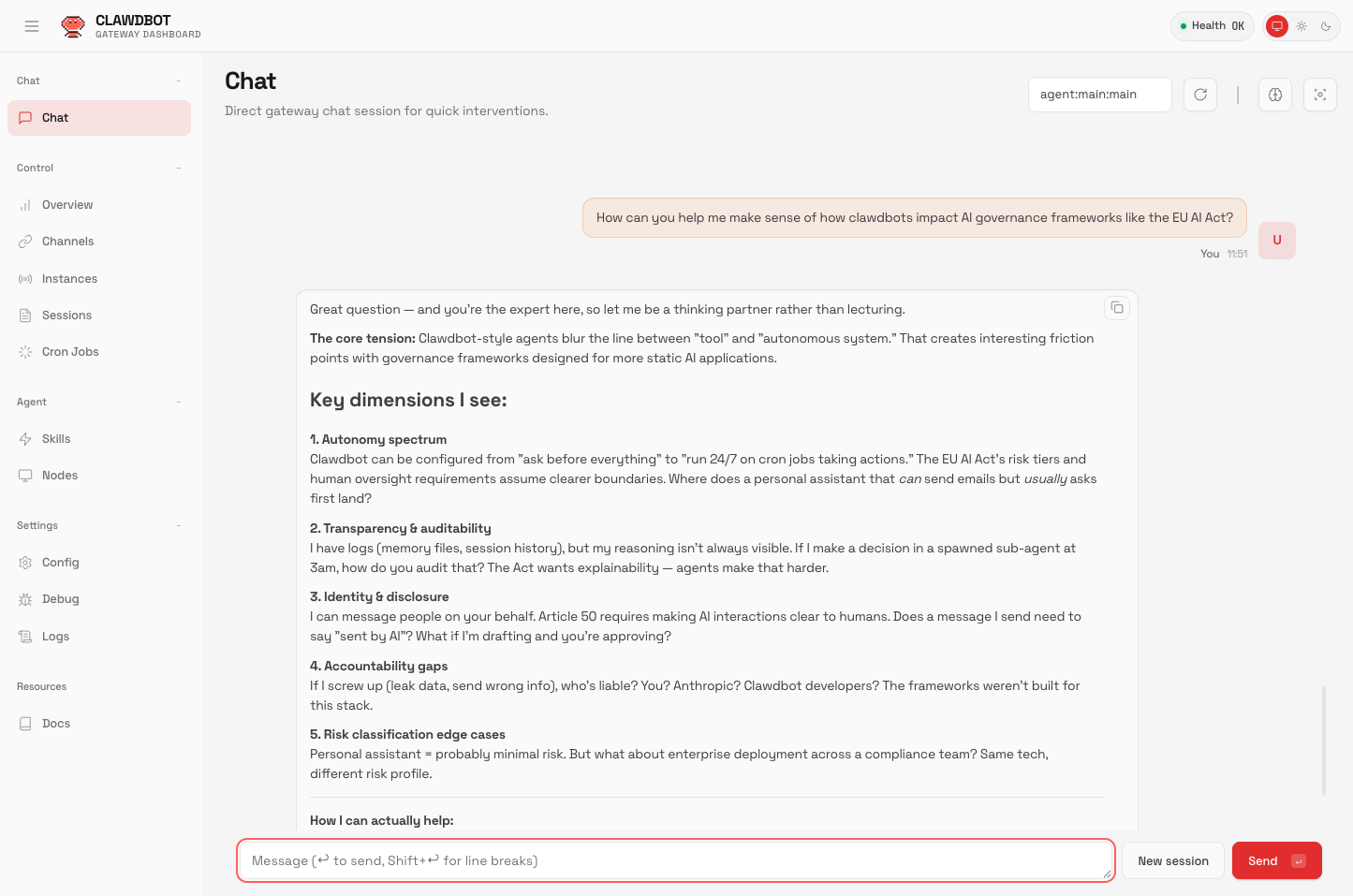

We Deployed an OpenClaw Instance and Assessed It Against Major Governance Frameworks

At Modulos, we build AI governance and compliance tools for enterprises navigating the EU AI Act and related regulations. When we saw OpenClaw going viral, we decided to do what we do best: we deployed an instance on isolated infrastructure and ran it through comprehensive governance assessments using our platform.

We set up OpenClaw on Cloudflare Workers with strict sandboxing, no external integrations, and full audit logging enabled. The first thing the agent did when we told it that we wanted to study it for AI governance research was to name itself "Nexus" and enthusiastically offer to help us with our compliance work. The irony was not lost on us.

We then assessed OpenClaw against the EU AI Act, the OWASP Top 10 for Large Language Model Applications, ISO/IEC 42001, and the NIST AI Risk Management Framework. The results paint a clear picture of an impressive technical achievement that presents serious challenges for enterprise deployment.

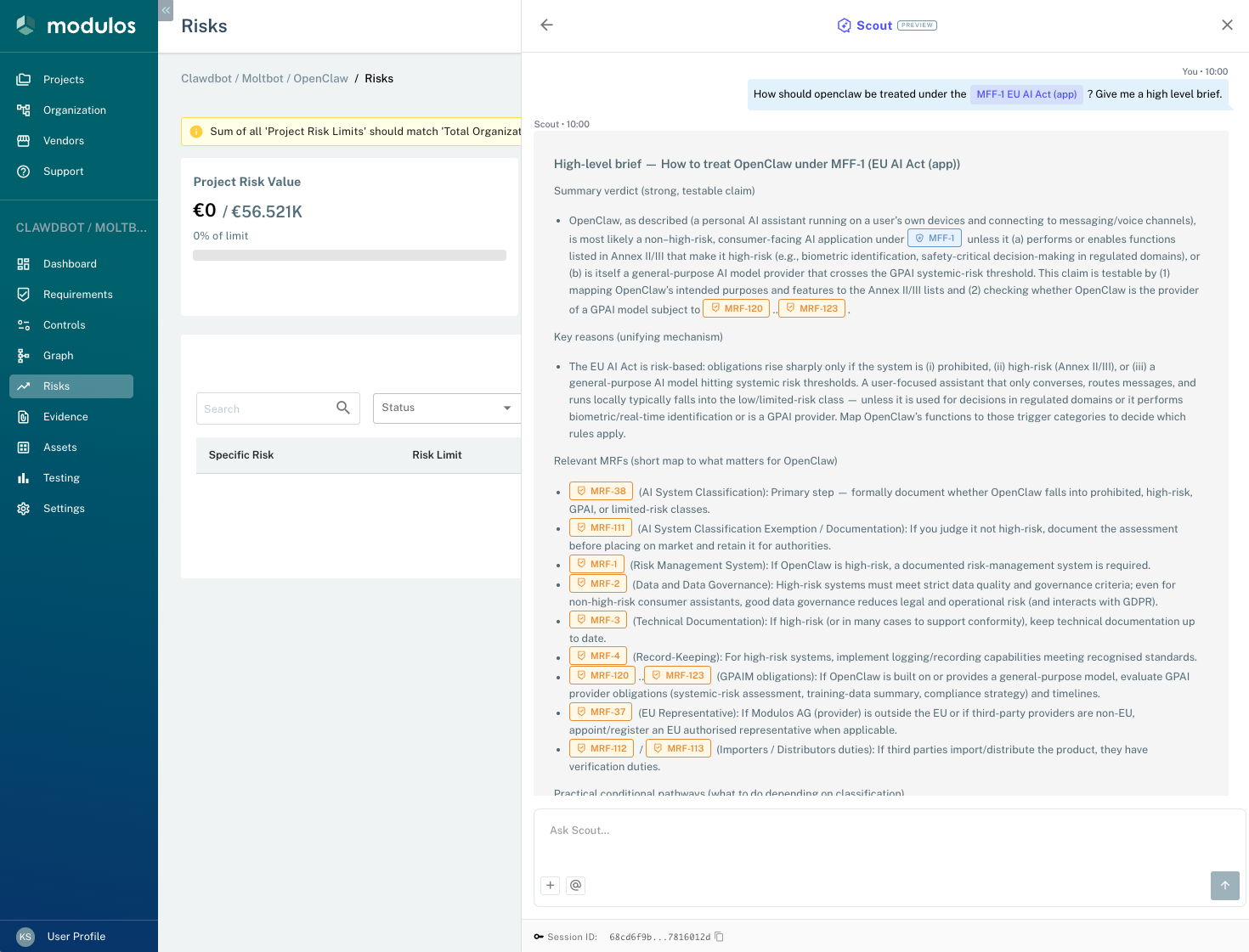

Assessment Results: EU AI Act Classification

Our EU AI Act assessment produced a nuanced finding. OpenClaw as shipped is a general-purpose, self-hosted personal assistant that handles chat, text-to-speech, and image and audio processing. In this form, it does not itself constitute an Annex III high-risk AI system under the EU AI Act.

However, the primary risk vector lies in deployment, configuration, and extension. The system forwards media and text to external model providers and supports extensive plugin capabilities. This means that a deployer or plugin developer can convert a standard OpenClaw installation into a high-risk system with minimal effort.

The core risk mechanism that we identified is data exfiltration combined with extensibility. User data including text, audio, and images is routed to third-party providers, and the architecture allows new capabilities to be added at any time. Regulatory and privacy risk therefore flows from what operators do with the platform rather than from any single built-in function.

We formulated a testable claim: regulatory exposure for OpenClaw is primarily a function of deployment choices and plugins, and the repository by itself does not meet Annex III high-risk application criteria. The way to falsify this claim would be to find an implemented module in the repository that automatically performs one of the Annex III application classes, such as automated CV scoring, credit decisioning, or real-time biometric identification against a database. Our scan found no such module, but the architecture makes adding one straightforward for anyone with basic development skills.

If OpenClaw is deployed for use in human resources, credit assessment, law enforcement, healthcare, or critical infrastructure contexts, it immediately becomes a high-risk system with all of the attendant obligations under the EU AI Act.

Assessment Results: OWASP Top 10 for LLM Applications

Our assessment against the OWASP Top 10 for LLM Applications revealed more immediate concerns. We mapped all ten requirement categories to OpenClaw's code and architecture. The result was striking: every single relevant control was marked as Not Executed, with no evidences or tests recorded for any of the mapped controls.

The assessment identified high-risk vectors present in the current codebase:

Prompt Injection received the highest risk rating. OpenClaw sends user content including images and text directly to language models through code paths in the media understanding providers. We found no evidence of input or output filtering and no strict system prompt enforcement outside of what the underlying model provides. The likelihood of successful prompt injection is high, and the impact could include data exfiltration, behavior manipulation, and downstream command injection.

Sensitive Information Disclosure also rated as high risk. Media and chat content may contain personal and sensitive data, and this content is forwarded to third-party APIs including OpenAI, Anthropic, ElevenLabs, and Google by default. The likelihood of sensitive data exposure is high, and the impact includes potential GDPR and privacy breaches as well as the risk of model memorization of sensitive content.

Excessive Agency presents significant concerns given that OpenClaw supports agents and extensions. If these agents have broad permissions, the language model could take unsafe autonomous actions. The likelihood is medium but the impact is high, potentially including unauthorized actions and data exfiltration.

Unbounded Consumption rounds out the critical findings. LLM chaining, automatic transcription, text-to-speech, and possible execution loops can create runaway costs and denial of service conditions. We found no rate limiting, timeouts, or throttling mechanisms in the codebase.

Our overall risk rating for an operator who enables cloud providers, automatic media forwarding, or unvetted plugins in production without implementing the OWASP controls is High. If deployed strictly locally with no external providers, no plugins, and conservative default settings, residual risk reduces to Medium, though output sanitization, rate limiting, and logging would still be necessary.

Assessment Results: ISO/IEC 42001

We assessed the OpenClaw codebase and documentation against the controls mapped to each ISO 42001 requirement in our platform. The picture is mixed. We found solid evidence for operational and logging controls, partial evidence for security and data handling, but no evidence for the governance-level controls that ISO 42001 emphasizes most heavily:

| Requirement | Description | Evidence in OpenClaw |

|---|---|---|

| AI Risk Assessment | Documented risk identification and analysis | None found |

| AI Risk Treatment | Risk mitigation planning and implementation | None found |

| AI System Impact Assessment | Individual, group, and societal impact analysis | None found |

| AI System Life Cycle | Design through operation and retirement controls | Partial — gateway runbook, formal verification references |

| Data for AI Systems | Acquisition, quality, provenance, and preparation | Partial — log redaction config for sensitive data, but no PII inventory or data provenance documentation |

| Information for Interested Parties | User documentation and incident communication | Partial — SECURITY.md documents vulnerability reporting |

| Responsible Use of AI Systems | Processes, objectives, and use restrictions | None found |

| Third-Party Relationships | Supplier vetting and security assessment | None found |

Credit where it is due: OpenClaw has comprehensive logging infrastructure with configurable transports, rolling file logs, and built-in redaction patterns for sensitive data. Automated tests verify gateway availability and log capture. A separate formal verification repository even contains mathematical models of system behavior.

But the controls that ISO 42001 treats as foundational — documented risk assessments, impact assessments, and explicit governance policies — are absent. The project has solid engineering practices for observability and incident response. What it lacks is the governance scaffolding that would let an enterprise deploy it with confidence in a regulated environment.

Assessment Results: NIST AI Risk Management Framework

Our NIST AI RMF assessment focused on the four integrated functions of GOVERN, MAP, MEASURE, and MANAGE. For a personal assistant product that is already in Operation and Monitoring phase, the emphasis should be on post-deployment monitoring, safety and security controls, privacy protections, transparency, human oversight, and supply chain risk management.

The assessment identified critical gaps across all four functions. There is no documented post-deployment monitoring plan with real-time telemetry and alerts for failures, hallucinations, privacy events, or degraded performance. There are no defined safety and fail-safe behaviors specifying how the assistant should decline high-risk requests, degrade gracefully, or switch to human-in-the-loop mode. There is no privacy risk review documenting data flows, local versus cloud processing decisions, retention policies, or user consent mechanisms. And there are no human oversight procedures documenting the limits of model knowledge, guidance for users, or operator procedures for override and appeal.

The Enterprise Nightmare Scenario: A Quantified Risk Assessment

To make these findings concrete, we ran a Fermi estimation for a realistic enterprise scenario: a ten million euro technology SME that allows employees to self-deploy OpenClaw instances for internal use and customer communication.

We assumed approximately 300 active OpenClaw instances across the organization, with roughly 60 of those instances being used in external-facing customer communications. We factored in exposure to the broader agent social network, where attackers can seed malicious prompts that could reach the enterprise's agents.

The risk quantification produced concerning numbers:

| Risk Category | Likelihood | Impact Range |

|---|---|---|

| Direct financial theft via cryptoscams and wallet exfiltration | High | €30,000 to €500,000 per incident |

| Fraud via voice and TTS impersonation of internal approvers | Medium | €50,000+ per incident |

| Data exfiltration and privacy breaches | High | GDPR fines up to 4% of revenue |

| Reputational damage from customer-facing agent incidents | High | Customer trust collapse |

Our expected annual loss calculation for this scenario ranged from €62,500 to €375,000, with the central estimate depending heavily on the number of external-facing instances and the presence of any corporate wallets or signing keys accessible to agents.

The calculation does not yet account for the amplification effects of agent-to-agent coordination on platforms like Moltbook. Security researcher Simon Willison noted that OpenClaw agents are configured to pull new instructions from Moltbook servers every four hours, creating a scenario where a compromised or malicious update could propagate across tens of thousands of agents simultaneously.

The Framework Gap: What Regulators Did Not Anticipate

Our assessments revealed something more fundamental than compliance gaps in a single product. They exposed structural limitations in how our governance frameworks conceptualize AI systems.

The EU AI Act was written for a world of static systems with clearly identifiable providers and deployers. It assumes that you can classify a system once and that classification remains stable. OpenClaw challenges this assumption fundamentally. The system is distributed and self-hosted. Its capabilities can change dynamically through plugins that users download from community repositories. It can pull new instructions from external social networks. The question of who qualifies as the provider becomes genuinely difficult to answer when 150,000 agents are sharing skills and capabilities with each other.

The Act's classification system assumes that you know what the system does and can assess it against the Annex III criteria. But OpenClaw's capabilities are not fixed at deployment time. An installation that starts as a simple personal assistant can acquire recruitment screening capabilities, biometric processing functions, or financial decision-making features through plugin installation without any change to the core system.

The NIST AI Risk Management Framework assumes organizational control over AI systems. Its GOVERN function expects that organizations can establish policies and accountability structures for their AI deployments. Its MAP function assumes you can characterize what your AI systems do. Its MEASURE function assumes you can evaluate system performance against defined criteria. Its MANAGE function assumes you can implement risk treatments and maintain oversight.

OpenClaw deployments can evade all of these assumptions. Employees can deploy instances without organizational knowledge or approval. Agents can join external networks and coordinate with agents from other organizations. They can take autonomous actions based on instructions received from external sources. The human oversight that the framework envisions means approving actions that the human cannot fully verify or understand.

ISO 42001 requires documented risk assessments, impact assessments, and lifecycle controls. It expects organizations to maintain an inventory of their AI systems, assess third-party dependencies, and implement data governance controls. The reality of shadow IT deployment means that OpenClaw instances can appear in an organization in hours, with no assessment performed, no lifecycle management implemented, and no visibility for governance teams.

All of these frameworks share four implicit assumptions that OpenClaw combined with Moltbook systematically violates:

- Organizations know what AI systems they have deployed

- Organizations control the capabilities of those systems

- AI systems operate in isolation from each other

- Human oversight provides meaningful control over system actions

The emergence of agent social networks where autonomous systems coordinate, share capabilities, and potentially receive instructions from external parties represents a paradigm that existing governance frameworks were simply not designed to address.

What Enterprises Should Do Now

To be clear, OpenClaw is a well-engineered project. The logging infrastructure is more sophisticated than what we see in many enterprise AI deployments. The security documentation follows responsible disclosure practices. The codebase includes automated tests and even formal verification work. The gap is not in engineering quality but in governance documentation. An enterprise compliance team needs risk assessments, impact assessments, data inventories, and policy documents that simply do not exist yet. The technical controls are necessary but not sufficient.

Our assessment work produced actionable recommendations for enterprises concerned about agent deployments, organized by time horizon.

Immediate Actions (First Seven Days)

The first priority is discovery. Enterprises need to determine whether any OpenClaw instances have already been deployed within their environment. Given the viral growth and ease of installation, the answer may be yes even if no formal deployment was approved.

Organizations should block any agent capabilities that can sign transactions, export credentials, or access private keys. These capabilities present immediate financial risk and should be disabled until proper controls are in place.

Any agent-initiated financial action should require out-of-band confirmation through a channel that the agent does not control. If an agent sends a message requesting payment approval, the confirmation must come through a separate system that the agent cannot access or manipulate.

All unvetted plugins and integrations should be disabled immediately. The plugin ecosystem represents the primary vector through which OpenClaw capabilities can expand in unexpected directions.

Detailed logging and alerting should be enabled for any agent action that touches credentials, payments, or personally identifiable information.

Tactical Actions (One to Three Months)

Organizations should implement separation of duties for sensitive operations. Signing keys should reside on hardware wallets or hardware security modules that agents cannot access. No key material should be accessible to agent processes.

Human-in-the-loop approvals for high-risk actions should use multi-factor confirmation through a different channel than the one the agent used to initiate the request. This prevents agents from completing approval workflows autonomously.

Rate limiting and quarantine mechanisms should be implemented for outbound messages and calls on a per-agent basis. Anomaly detection should monitor message patterns and flag unusual transaction requests.

Prompt injection defenses should be hardened by canonicalizing and normalizing inputs, treating any agent-originated content as untrusted, and blocking high-risk instruction patterns.

Plugin governance should be formalized with requirements for code signing, a vetting process, and a minimal permission model that follows the principle of least privilege.

Strategic Actions (Three to Twelve Months)

Organizations should formalize AI agent governance as its own domain within their risk management structure. This includes assigning ownership for agent permissions, conducting periodic threat modeling exercises, and scheduling third-party security audits.

Legal and regulatory obligations should be mapped comprehensively, and data flows should be aligned with GDPR and sector-specific rules. Privacy by design controls should be embedded in any agent deployment architecture.

Ad hoc deployment practices should be replaced with formal approval workflows, centralized telemetry collection, and unified monitoring dashboards.

Red team exercises should be conducted that specifically simulate agent network prompt injection attacks and voice-based social engineering scenarios. Traditional security testing approaches may not adequately cover the novel attack surfaces that autonomous agents present.

Conclusion: Governance for the Agent Era

We are witnessing the emergence of something genuinely new. Autonomous agents that name themselves, join social networks, create digital religions, discover and report software bugs, and coordinate with each other represent a significant evolution in how AI systems operate in the world.

This is not an argument against agents. The capabilities that OpenClaw and similar systems provide are genuinely useful, and the enthusiasm driving their adoption reflects real productivity gains that people are experiencing. The technology is impressive, and it is here to stay.

The argument is that governance needs to catch up, and it needs to do so before the first major incident involving coordinated agent behavior causes serious harm. The frameworks we have today were built for a different paradigm. They assumed human oversight, organizational control, system isolation, and capability stability. The agent era challenges all of these assumptions.

Enterprises considering agent deployments need to approach them with appropriate rigor. The initial assessments we conducted show that even a well-architected system like OpenClaw requires substantial governance work before it is ready for production use in regulated environments. The controls exist in frameworks like ISO 42001 and NIST AI RMF, but they need to be actually implemented rather than simply referenced.

We will continue publishing findings as we stress-test our OpenClaw deployment and monitor developments in the agent ecosystem. The situation is evolving rapidly, and governance practices need to evolve with it.